Coming in the next week or two, Travelball Select National Championship coverage. What a performance last weekend as Lamorinda from Northern California won their second straight National Championship. Last year they won the 11U title over North Texas; this year, six of the same kids came back and they won in a re-match. Highlights coming soon.

The last couple of months have been my busiest in quite some time. So, over the Fourth of July, I am going to take a break and enjoy a little vacation at St Simon’s Island on the Georgia coast.

Then, of course, we turn or attention to preparing for another amazing Georgia high school football season.

I was thinking this morning about the proper way to post here on the site with the holiday coming up and it hit me. I already have my patriotic story. Three years ago, I had the good fortune of writing a feature piece on some extraordinary Americans. I hope you enjoy reading this as much as I enjoyed putting it together. I’ll post this piece today and again the week of the Fourth.

The intersection of Peachtree Avenue and Forsyth Street near Five Points

Photo courtesy of AJC Collection at Georgia State University Library

The impact of WW II on Atlanta and its People

By CHRIS MOONEYHAM

The streetcars passed by the restaurant as the fry cook slid his nickel into the jukebox. With war raging on the other side of the world he was in the mood for something upbeat. As Glenn Miller’s newest hit, Chattanooga Choo-Choo, bellowed through the air, the war was coming home to his beloved Atlanta.

Jack Fortis was a 14 year old, wide eyed young man; working his first job in the city he loved. Unexpectedly, his boss burst through the doors and said, “Turn off the horn man and put on that radio.” Fortis saw a look in the stern tactician’s eyes he had never seen before and knew something was wrong.

“He was the sternest and straightest man I have ever known,” said Fortis, “but at that moment he looked down right scared.”

So, before Mr. Lattimore could return from the back of the establishment to find Fortis standing in amazement, the young man reached for the knob of the transistor radio. Today was the beginning of yet another wave of economic and population growth that would change the city of Atlanta and its inhabitants forever.

It was Sunday, Dec. 7, 1941.

On the east side of town, near the intersection of Flat Shoals Road and Glenwood Street, Bill Bennett, the middle man of nine children, instantly drew a sick feeling in his stomach. At the tender age of 17, he would enlist in the war effort and join the Navy.

In Calhoun, a small town in North Georgia about 70 miles from downtown Atlanta, eighth-grader Annie Irene Lewis and her classmates were ushered into Calhoun High School’s library for an announcement. “When the administrator told us about Pearl Harbor, all I could think about was my brothers.”

Her brothers, Ralph and Herman, were both members of the National Guard. It was now apparent that both men were going to war. For that reason, Ralph and Herman Lewis returned home for Christmas before being shipped out.

It could be said Herman Lewis was the first casualty for Calhoun in World War II. While on his Christmas leave, during an apparent hunting accident, Herman was wounded and died from his injuries. He was only home because of the Japanese attack.

By the middle of 1942, Ralph Lewis was in the Philippines.

______________________________________________________________________________

Throughout its history, the South’s largest city, and its people have mirrored each other by responding to and overcoming economic hardships. Originally known as Terminus, the train depot was created in 1837, in part, to raise commerce, foot traffic and spending. It did just that.

By 1865, Atlanta’s 10,000 inhabitants were in a rebuilding mode; after General Sherman burned 70 percent of the city to the ground.

The growth was slower this time. The train tracks were replaced. South Georgia’s agriculture eventually came back to the city for trade and shipment; and the industrial revolution was about to be in full swing.

Like every city in America, the depression of the 1930s hit the city hard. This time Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal was the savior. The construction of new roads and highways was a focal point. Most important, these projects employed local residents.

Grants were given to city commissioners with specific designs on improving businesses that may benefit the government, such as the improvements to Candler Field, on the south side of the city.

The groundwork was laid for Hartsfield Airport.

At the time of the attack in Hawaii, Atlanta was a friendly Southern city trying to establish its place among the great cities of the nation. The metro population was just over 800,000 and made up of just 10 counties.

Throughout the war effort, many Southern cities would expand industrially to manufacture war supplies.

The city of Marietta is a case study in the government aided expansion of the metro area.

In 1941, FDR initiated a series of airport construction programs to ready the nation for its impending participation in the war. The bonds helped modernize Rickenbacker Field in Marietta.

The government made a conscious effort to move military manufacturing to the interior of the nation and away from traditional port cities.

Atlanta, with its train terminals, newly redesigned Candler Field, and newly constructed highways leading to the suburbs, was a logical choice.

Bell Aircraft Corp. came to Marietta and churned out nearly 700 B-29 bombers from the spring of 1943 to September of 1945. Average employment at Bell was 25,000, and eight out of 10 employees were Southern or native Georgians.

Photo courtesy of archive at The Atlanta-Journal Constitution

_____________________________________________________________________________

While some Atlanta natives were headed to the suburbs to work, others like Annie Lewis went downtown to live out the war and help boost the city’s economy.

Lewis said, “Well, we all wanted to do our part. Some women went from secretary work to working in the factories. I was not cut out for the factory, but I could fill that other women’s position. So I filed papers and did clerical work.”

The month she turned 18, Lewis moved downtown and found an apartment at the corner of Ponce de Leon Avenue and Boulevard; just one block from her first job at the famed Sears & Roebuck Co.

She lived the typical life of a young woman in downtown Atlanta.

“We would go to a skating rink right down the street from the Fox Theatre,” she said. “We’d also go down to the park and swim. That wasn’t my favorite; I didn’t like the way I looked in a bathing suit. But that’s what we did at that age…socialize.”

By this time Bill Bennett was at Barin Field, in Alabama, near the small town of Foley. After enlisting in the Navy he was assigned to Aviation Ordinance. With Foley, and the base, only a short distance from the Nazi-infested waters of the Gulf of Mexico, Bennett and his men had an interesting perspective on the war.

“One day we saw some men we had not seen before, in a situation we had never seen before. They had K-9 dogs out and were searching the woods. The rumor around the base, and in Foley, was that someone had seen some Nazi’s come ashore in the Gulf. Of course, they never told us for sure and we never saw any Nazi’s either.”

There was one constant most people lived with in America at this time. The possible death of a loved one, a friend, or anyone war related was always present. Bennett recalls a conversation he had with one of his best friends in the service.

Bennett said, “I walked in to the room and saw Grant crying. I said ‘What’s the matter with you?’ He told me that he just found out his brother had been killed in the Pacific…on some island called Peleliu. They told him, if he wanted, since he was the last son in the family, that he leave the service and could go home. And he did.”

Back in Atlanta, Jack Fortis was not yet 18 and was unable to enlist in the Army.

“Everywhere you turned there he was, Uncle Sam. I felt like he was staring at me; pointing at me with that finger. I nearly got hit by the streetcar three times in one day because I was staring back at him. I just wanted to scream at him, ‘Hey look, I want to get over there and help, but they won’t let me in’.”

Remarkably, Fortis tried to enlist four times in four different Georgia cities. He was turned away each time.

When not being hunted by the gray bearded man in blue, Fortis noticed his city changing. “The streets were always packed. Everyone was going somewhere and seemed to have a purpose. Businesses were opening up left and right.”

Later he added, “There was a real feeling of a united front. I do not know if this is true statistically, but I swear crime went down also. It was like the criminals were too busy helping out to con anybody.”

Diners, like the one where Fortis manned the skillet, became central locations to pick-up information on the war effort.

Lewis said, “All we did, as young people, was hang out at the diners late at night. Places stayed open all night long to serve all the workers that had poured into the city. If you wanted to know what was going on with the war, all you had to do was ask.”

______________________________________________________________________________

Three days provided detailed, vivid memories for the Atlanta natives.

Fortis said, “The day FDR died was tough. I asked Mr. Lattimore if we were closing and he said ‘son there are only two things people want to do when they are this sad: drink or eat.’ So we stayed open.”

Lewis added, “We were let out early from work the day the president died and didn’t work the next day either. I’ll never forget the black bands and white flowers in the shop windows.”

On the day the German’s surrendered, Bennett remembers the celebration. “We all decided to go into Foley. We heard they were giving away free beer in town. Of course, by the time we got there, they were out.”

On VJ Day, when the Japanese surrendered and the war was officially over, Bennett remembers guys started counting their “points” to see if they were ready to be discharged. He added, “There were a lot of guys who had been there longer than me; so I knew I would be one of the last ones out.”

Downtown Atlanta on VJ Day was pandemonium. Much like every other American city that day, the celebration poured into the streets.

Fortis was right in the middle of it. He said, “The first I knew about it was when I saw papers being thrown from buildings. I saw people running and shredded paper falling on their heads.”

Lewis was in the bathtub at the time. She said, “When I first heard the commotion I thought we may be under attack. I could hear women crying in the street.”

She then reached for a towel, covered herself as best she could and peaked out the window to the street below. She said, “I thought to myself, ‘lord, the war is over’. So Bonnie and I put on our best dresses and went to celebrate. It was really something. We were all happy, but it changed us.”

______________________________________________________________________________

After the war, the Bell Bomber plant became Lockheed-Martin; continuing to employ local men and women.

Also after the war, the government took over Rickenbacker Field and kept it in operation. They would re-name the installation Dobbins Air Force Base.

Finally, the national government helped finish the construction of U.S. Highway 41 and other road projects; and the migration to the suburbs by people from downtown would truly escalate.

By 1950, the influx of industrial and government workers to the area raised population in Cobb County by more than 60,000 and metro Atlanta by more than 200,000.

______________________________________________________________________________

A few years later, Lewis would meet her future husband in Atlanta and move back to the suburbs. She would have three children and six grandchildren and today resides in Marietta.

Her brother Ralph returned home from the war safe and sound.

Bill Bennett served, in his own words, “three years, eight months and eleven days!” Afterward, he returned to East Atlanta, and shortly thereafter had a conversation with his father about his future. “He told me I should become an electrician, because they get paid more than anybody and work less than anybody. He was wrong on both accounts.”

Bennett became an electricians apprentice and began climbing the ladder. He retired after 37 years of owning his own business.

However, the best decision he made following the war was to attend the YWCA Ball for Ex-Servicemen. It was there Bennett cut in on a Yankee sailor to steal a dance from a girl named Nell. She showed him little interest at first, though today she admits he was the most handsome man at the ball.

They have been doing the jitterbug together ever since.

Bill and Nell have been married 64 years and have been blessed with five children, 13 grandchildren, and eight great-grandchildren. They live in Lilburn.

______________________________________________________________________________

Today, metro Atlanta has become the example of urban sprawl. The metro area is comprised of 28 counties and a population of just about 6 million.

At the current rate, it is estimated by 2040, the population will reach the 8 million mark.

As for Jack Fortis, he never made it to enlistment. When the war ended he was a month from his 18th birthday.

“Just as well,” he said, “I spent a lot of time walking around the city. I never liked change. If I had left here I might have gone crazy. Sometimes I think people don’t realize just how different it was.

Boy, did that war ever change this town.”

SIDEBAR

Local sports provided more than war time distraction

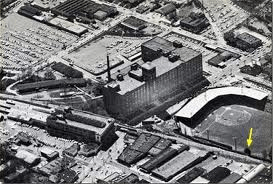

Aerial view of Ponce De Leon Park and the famed magnolia tree in centerfield

Across the street is the Sears and Roebuck Building

Photo courtesy of BaseballFever.com

As legend has it, the manager of the minor league Atlanta Crackers, Kiki Cuyler was not a fan of the large magnolia tree that stood in centerfield of old Ponce De Leon Park. When anyone, from either team, would hit a ball into the tree he would let fly obscenities that would make the ball players blush.

However, during the days of World War II, he spoke of the famous landmark with reverence.

In the winter of 1942, the commissioner of major league baseball, Kenesaw Mountain Landis sent President Roosevelt a letter questioning if the games should continue. The president felt it was imperative for all sports to continue; not only for the economic impact and to keep people working, but also for the psyche of the American people.

FDR’s response, known as the “Green Light Letter,” was sent to Commissioner Landis.

So the games went on and fans in Atlanta and the state enjoyed a good bit of success.

Long before the Braves came south, Atlanta’s heart truly belonged to a minor league baseball team. The Crackers were arguably the most famous of all minor league teams. From 1895 to 1965, the team won an astounding 15 league championships. Major league teams fought and bid for the right to be an affiliate of the team.

During the war years, the team rebounded from a sub-.500 record in the first two years, to three consecutive first place finishes and a league championship in 1946.

Atlanta history buff Priscilla Pennington adds, “The Crackers were not only important for leisure, but also for revenue and jobs security. Countless stadium workers truly relied on the second income to provide for a family whose father, or main bread winner, was in Europe or the Pacific. At one point, most of the stadium personnel were boys not old enough to enlist.”

The club was one of the first jobs for Hall-of-Fame sports broadcaster Ernie Harwell. The Southern gentleman called Cracker games from 1943 to 1949. Before the start of his last season, he was contacted by the Brooklyn Dodgers. Since Harwell was under contract, Branch Rickey, Brooklyn’s general manager and the man who brought Georgia native Jackie Robinson to the majors, traded for Harwell.

On the gridiron, the Dawgs and Jackets combined for some of their best seasons in the 1940s. In fact, in 1942 the University of Georgia won the National Championship led by a young Charlie Trippi and a man who captured the sporting public’s attention, Frank Sinkwich. The senior combined for 40 touchdowns that year and won college footballs coveted Heisman Trophy.

The Heisman Trophy is named for a former Georgia Tech head coach, and the Jackets had a great run of their own in the early part of the decade. From 1942 to 1945, the Jackets won two Southeastern Conference championships and a combined 29 games.

The success of both schools was followed by veterans all across the world while at war; and led to many of these men enrolling in school when they returned home.